The History of Asphalt Shingles

Who invented the asphalt shingle? Technically, it was Henry Reynolds of Grand Rapids, Michigan, who took a roll of roofing material and cut it into the first shingles in 1903. However, the history of asphalt shingles is not one of a single person’s accomplishment. Instead, a series of roofers, manufacturers and outside organizations all contributed to the development of the asphalt shingle as we know it today. They all tried to improve roofing materials in the face of rain, wind, hail, and other environmental threats.

In order to truly understand the major developments that have made asphalt shingles one of the most popular building materials ever, we have to start all the way back in the 1800s.

Pre-Asphalt Shingle Roofing

In 1800s America, roofing looked much like it had for centuries beforehand. There were a few different material options for roofing on homes: wooden shakes, clay tiles, slate tiles, and metal roofs. Today, these roofing materials can still be seen on historic homes. At the time, material availability and costliness determined what any given homeowner might have had on their roof. In fact, homes in poorer neighborhoods may have still had thatch for roofing, a straw or hay material found on many ancient roofs.

However, in the 1840s, Samuel M. and Cyrus M. Warren, from Cincinnati, began to use a cotton fabric for roofing. They took the fabric and used it as the base or “mat” of the roofing material. They coated the mat with pine tar and sprinkled sand on it. This material offered some protection from moisture and quickly caught on. To improve on their product, the Warren brothers switched over to using coal tar, which was cheaper than pine tar.

Much later, in the 1860s, market conditions changed again, making coal tar an expensive option. The Warren brothers found that the new petroleum industry was producing asphalt, a useful material for their purposes. So, they began to use asphalt to coat the fabric. They also switched to slate granules instead of sand.

It wasn’t until 1903 that Henry Reynolds began cutting this material up into individual shingles. By doing so, he made application easier and improved the look of the roof. As with many early inventions, there are other companies and people who claimed to have been making shingles around the same time.

The Growing Popularity of Asphalt Shingles

Many roofers began cutting up this early roofing roll material into shingles. Then, in 1911, the National Board of Fire Underwriters sought to raise awareness of wood shingles as major fire hazards. Asphalt shingles were a great alternative that had significantly reduced fire risk.

Other roofers began to cut out shingles from the roll material with roller dies to copy Reynolds. The technological advancements in manufacturing machinery helped reduce costs and allowed roofers to keep up with demand for these new shingles. Then, roofing manufacturers caught on to the shingle trend. In the 1920s, Bird and Son offered the first strip shingle. They called them Neponset Twin Shingles and boasted that the product had reduced installation costs and fewer cracks and nail holes. It also mimicked the look of slate roofing.

These shingles were only available in “soft” red and green. These were the natural colors of the locally available slate that Bird & Son crushed and added to the top of the shingles. Red and green remained the only color choice until shingle brands came out with ceramic granules which could be essentially any color. If manufacturers used just one shade of slate, the natural tint differences in the material would be noticeable. Instead, they spread in granules of many slightly different shades of the main color to appear more consistent overall. This trend continued for ceramic shingle granules which were developed later on.

Manufacturers created the sense of depth and dimension on the shingles with these granules. Specifically, a strip of dark (black) granules was laid down during the shingle manufacturing process in the area on the shingle which would be immediately beneath the lower edge of the overlying shingle once installed on the roof. This dark “shadow band” would convince the human eye that the shingle is quite thick, as it appears to cast a ‘shadow’ on the shingle below. Shadow bands in recent years have tended to be more subtle (often utilizing granules that are not pure black). Pure black shadow bands were considered by some to be too obvious. Another concern is that if the width of the dark granule band often varied slightly, which happened often in the normal shingle manufacturing process, then the overall roof appearance would look odd and inconsistent. More subtle shadow bands reduced this aesthetic risk.

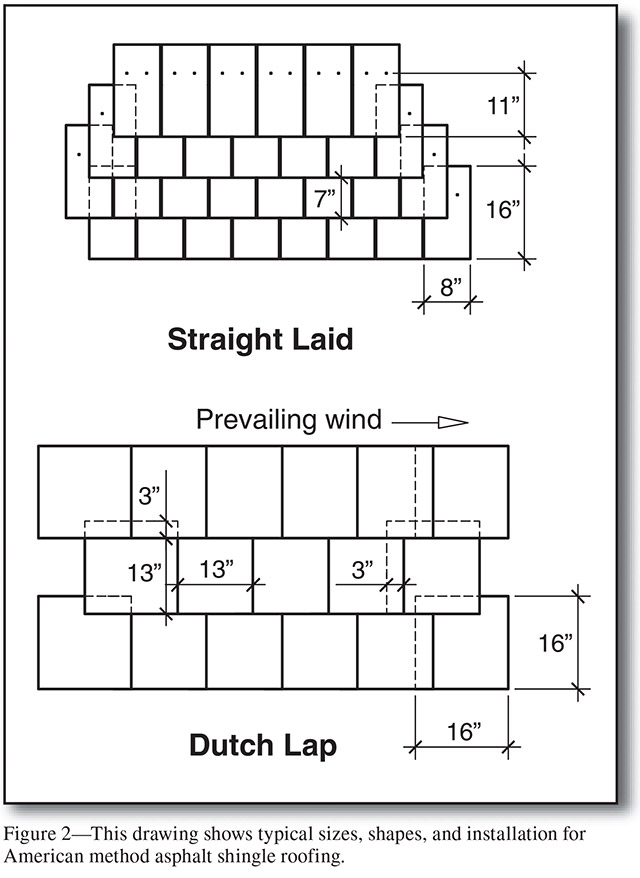

Early shingles were also installed differently than today’s shingles. In the 1920s and 1930s, the shingles were single pieces, either square or rectangular. While there were other shapes in the European market, American shingles were mostly “straight” or rectangular. These were usually Straight laid. Some were Dutch Lap laid, which involved a larger shingle exposure and an additional horizontal overlap between shingles.

However, in 1935, shingle brands released the first three-tab shingles, which were the industry standard 12 inches by 36 inches. They were installed Straight style, overlapping vertically but not horizontally, just as they are today. By the 1950s, this size would become standard across most shingle manufacturers.

Then, in the 1970s, Canada adopted the metric system. IKO began offering larger shingles at this time. The innovative “metric shingle” is 39-3/8 inches wide by 13-1/4 inches long. Those are unusual dimensions in Imperial, but in metric the shingle is a straightforward 1000 mm by 337 mm. These larger shingles mean that roofers need fewer shingles needed per roofing square. In addition, these shingles make a more significant visual impact and are faster for roofers to install.

Shingle popularity continued to grow in North America over the next few decades. By 1939 there were 32 manufacturers who produced 11 million squares of shingles.

Early Shingle Materials

The earliest shingles had the same three components that they have today: a base reinforcement material called a mat, asphalt and a mineral granule top surfacing. However, each material used for this component has changed over time to provide better roof performance and safety.

For example, in the 1940s, the roofing industry moved away from the cotton rag mats that the Warren brothers had started with. Shingle manufacturers instead began to use an organic material that was very tough as the base for the shingle. The organic mat was saturated with a soft ‘saturant’ asphalt as well as coated on top and bottom with a harder weathering asphalt.

Then, in the 1970s and 1980s, some shingle manufacturers switched over to inorganic fiberglass for the shingle mat. Fiberglass was thinner yet stronger and weighed less than organic mats. Unlike organic mats, fiberglass mats did not require the saturant asphalt, as the mats are inherently resistant to moisture absorption, and asphalt shingles made using fiberglass mat are also more resistant to fire. All shingle manufacturers soon followed this trend, and fiberglass mats are now industry standard.

The materials shingles are made of continue to be improved to this day.

Multi-layer Laminated Shingles

Prior to the 1970’s, almost all shingles were cut from a single layer of roofing material. During the manufacturing process, the various areas of colored granules were dropped into the hot coating asphalt of the roofing web and pressure rolls were used to embed the granules into the asphalt before it cooled. Manufacturers created a gradual transition of color from one granule area to another. Many homeowners became accustomed to these softer shingle color blends with muted tone transitions between the shingle’s lighter and darker areas. In the 1970’s more modern tastes called for a sharper transition between the colors. To achieve this, laminated shingles were introduced.

To make laminated shingles two layers of material are adhered together. There is a top “tooth” layer of roofing sheet and a bottom “continuous shim” layer. The granule colors on the tooth layer are not likely to coincide exactly with granules on the shim layer. The result is a more highly contrasting and sharply defined shingle coloration, and once installed on the roof, these laminated shingles more closely simulated a slate, tile or wood shake appearance.

Homeowners were quick to appreciate this aesthetic improvement of laminated asphalt shingles. Roofing contractors also gained an advantage from these new shingles. Three-tab shingles required extra care and measurements to align the shingles just right and create the “brick-like” appearance. Although laminated shingles also require specific shingle offset and exposure dimensions, the random multi-layer aspect of modern laminated shingles offers more forgiveness for minor roof adjustments, and so installation is simpler to a certain extent.

Manufacturers initially made laminated shingles by a batch ‘off-line’ process, but with advancements in manufacturing equipment, the process is now continuous. Ribbons of tooth and shim material are cut, overlaid and laminated together. Then a machine cuts the combined material into individual shingle lengths. Over the years manufacturers have also introduced many creative cut patterns, color blends, shadow bands, and even a third layer to some laminated shingles.

Weather Challenges

Asphalt shingles provided many desirable characteristics that homeowners could appreciate, from waterproofing to beauty and fire resistance. However, in the mid-20th century, some increased weather conditions were still a large challenge for the roofing industry to overcome.

One of the biggest issues with early shingles was their ability to resist strong winds.

Prior to the 1950’s asphalt shingles were often manually glued down with asphaltic adhesives to help them resist wind uplift. In the late 1950s, manufacturers created self-sealing shingles. At the manufacturing plant, adhesive asphalt strips were applied to the back of the shingles. This innovation allowed roofing installers to save the time, mess, and expense of on-site adhesives. After exposure to the sun, these self-sealing shingles stuck to the shingles in the adjacent course and could better resist wind forces.

Manufacturers have continued to improve on the adhesives they use on shingles. Early adhesives were based on harder asphalt resins, but with the advent of fiberglass shingles, a stronger and ‘stickier’ sealant using asphalt combined with select polymers has been found to provide better staying power in high winds.

Hail is another concern a home’s shingle roof must contend with. In the 1960s, the insurance industry was increasingly concerned with roof performance during hailstorms. Underwriters Laboratories and the Institute of Business and Home Safety partnered to create an impact-resistance classification system for roofing materials including asphalt shingles.

Today, there are two common industry impact tests. One is UL 2218 which uses steel balls dropped from a certain height onto a shingle test deck. The other is Factory Mutual (FM) 4473 which launches ice balls of various diameters at shingle test decks. Both test methods yield a four-class system, with Class 4 shingles being the most resistant to impact.

Asphalt shingle wind resistance testing has also evolved over the last three or four decades. Originally, the only industry test to assess wind resistance involved a deck of asphalt shingles, installed per the manufacturer’s instructions, and conditioned in a large oven to permit the self-sealing adhesive to activate. The deck was then placed in front of a large fan which blew air (wind) over the deck.

This intuitive fan-induced wind resistance test still exists today (ASTM D3161) but the industry has used advanced scientific engineering principles to more accurately a shingle’s inherent uplift resistance (ASTM D6381) and sealant bond strength. By evaluating these two shingle properties together, the overall theoretical wind resistance of an installed roof system can be determined (ASTM D7158). The test method yields a grading scale with the highest classification of Class H equating to an estimated roof wind speed of 150 mph.

The Future of Asphalt Roofing

So far, the story of asphalt shingles is one of long-term development and response to consumer needs and environmental challenges. In looking to the future, roofing manufacturers are designing performance shingles performance shingles that can help with the challenges we face through climate change.